Dear friends and readers,

Appreciating the moon (赏月) is a particular flavor of Chinese romanticism. Countless Chinese poets have spilled ink over what it means to look at the moon, and for the majority of them, the consensus is that looking at the moon evokes a longing for a place where you were once from, with the people you once knew.

In arguably the most famous verse about the moon (静夜思, roughly translates to “Musings in a quiet night”), Tang dynasty poet Li Bai (唐:李白) pondered: I looked up to the bright moon, and when my gaze lowered I thought of my home. (“举头望明月,低头思故乡。”)

Similarly, many other verse from other poets follow this sentiment.

Song dynasty philosopher Wang An Shi (宋:王安石) exclaimed: The passage of time brought forth another splendid spring, but when will the moonlight bless my journey home? (“春风又绿江南岸,明月何时照我还?”)This verse juxtaposes the liveliness of spring with moonlight, painting that the beauty of nostalgia is privileged over the beauty of the seasons.

But others offer a much starker image of the moon by situating it in autumn. From Tang dynasty poet Du Fu (唐:杜甫):Tonight is the night when dews and frost whitens, but nothing compares to the bright moon in my homeland. (“露从今夜白,月是故乡明。”) Here, the depiction of loneliness and sadness through the season changing reinforced the metaphor of a moon as a reminder of comfort.

Beyond the seasons, the moon is depicted as an eternal shrine to revere. Again from Li Bai: The people of today can never see the past moons, but the moon of today once shone on past people. (”今人不见古时月,今月曾经照古人。”)This verse evokes a sense of grief, loss, but also an honor to heritage, channeled through the moon as a bridge across time.

The moon not only connects people across time, but it also connects people across space. From Tang dynasty poet Zhang Jiu Ling: The bright moon rises above the sea, and all that graces the horizon share this moment.(“海上生明月,天涯共此时。”)No matter where we are, we are all under the same moon, and that brings a comforting thought.

As we get taught these ancient verse, we collectively accrued cultural memories of the moon. A reminder of home, a reminder of comfort, a reminder that we are all connected: past, present, everywhere, all at once.

Mid-Autumn Festival

One of the four core Chinese festivals is the Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋节) taking place the 15th day, 8th month of the Lunar Calendar. On that day, the moon is the brightest and roundest of the entire year.

Appreciating the moon, naturally, is one of the main cultural norms of this festival.

We look at the moon with our loved ones.

We appreciate its brightness, its roundness, and its freckles. We appreciate its sight, and in turn, we appreciate the people around us, the people who are away, the people who are gone, and the people who we’ve yet to meet.

With a festival as ancient and storied as the Mid-Autumn Festival. The cultural norms are countless. Perhaps one day I will write about the others, but the other one I have to bring up, is eating mooncakes (月饼).

Mooncakes

Mooncakes are Chinese pastries meant to commemorate the moon. In its meaning, mooncakes are carry the meaning of togetherness and unity. The Chinese phrase for this meaning, “团圆”, evokes physical roundness as well, which both full moon and mooncake embodies. Inherent to this pastry is the idea of sharing: you must share the roundness of the pastry as you share your companionship with others. There are many different types of mooncakes, but they all share a few criteria: they are often round, they are easily transported, they are shareable, and they are sentimental gifts to loved ones.

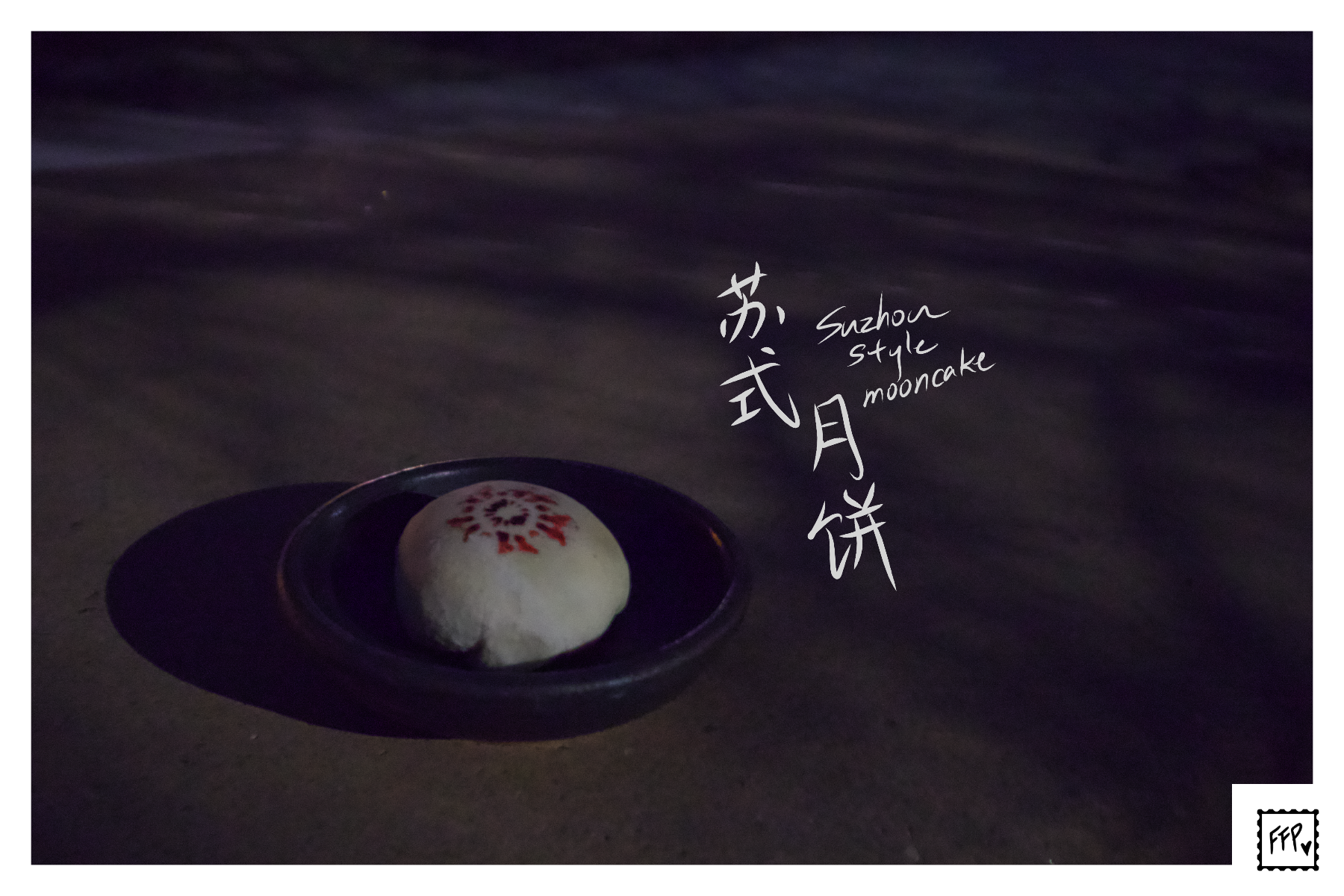

From Shanghai and surrounding regions (江浙沪, a short-hand for Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai), the local mooncake is a Suzhou-style mooncake (苏式月饼). These mooncakes are often round, flaky, lard-laminated pastries filled with a flavorful pork filling. Classic to the region’s taste, the overall pastry is optimized for umami (鲜味) using sweetened soy-sauce, and locally it’s more often called umami pork mooncake (鲜肉月饼). It’s certainly less known to the western audience, probably because its filling choice demand local production; something that the Cantonese-style mooncakes (广式月饼) do not suffer from.

I do have a recipe from my mother on this, however, I totally crashed and burned on it, namely because my mom had her recipe in volume measurements, and I interpreted her recipe with weight measurements. Because I have some compulsive tendencies about baking with weight measurements, I decided to test another a recipe out to incredible success (sorry mom).

The pastry was well-laminated, the pork was seasoned just right, but it was slightly raw on the bottom because I was overly concerned about closing the bottom that I clumped too much dough on the bottom.

This weekend, I have decided to make this recipe again.

What I love about making Suzhou-style mooncakes is the lamination method. Unlike the French lamination techniques, Chinese lamination uses lard dough (“油酥”) instead of butter, which forgoes aroma but emphasize the tenderness of the pastry. You wrap the lard dough inside of a piece of dough, roll it out, do a letter fold, and then flatten it out into a large sheet. The critical difference here is that Chinese pastry roll up the flat sheet, instead of creating more folds like the French. This makes a long tube of lard dough spiral that can be then portioned and rolled out into wrappers for fillings. When made into a proper wrapper, all the exposed lamination is folded inward. In this lamination technique, you see the different ideals of the two laminations; the French folds prominently shows off the layers and aroma of the butter in shining beautiful golden brown, but the Chinese rolls hides the layers to maintain a delicately pale appearance until the surprising tenderness of the first bite.

The other little detail I decided to add this time is a color stamp. Because of the paleness of the pastry, a color pop is often added with a red stamp. Here I have used a Cantonese mooncake peach blossom mold and red food coloring to make a pattern, but I will badger my mom to bring some actual nice stamps ones back from Shanghai.

Unfortunately, tonight was a moonless night (I had missed the proper timing to be writing this postcard), but I managed to find a street lamp that casted a white glow, almost in the spirit of moonlight. In this view, the mooncake seem to take on the visual qualities of the moon, with its pale, white, cratered surface glistening.

Of course, I took this photo, and then sent it to my family.

Signed and delivered,

Cheers,

Jeff